With its demography and economy, Asia will be able to help shape the future process of globalization. But it must first deal with its festering territorial disputes and acute competition over natural resources.

By Brahma Chellaney

Vanguardia Dossier, Number 41, October-December 2011

(Original in Spanish)

Asia, home to more than half of the global population, is likely to help mold the future course of globalization. In fact, with the world’s fastest-growing economies, the fastest-rising military expenditures, the fiercest resource competition and the most-serious hot spots, Asia holds the key to the future global order.

Asia has come a long way since the time two Koreas, two Chinas, two Vietnams and India’s partition occurred. It has risen dramatically as the world’s main creditor and economic locomotive. The ongoing global power shifts indeed are primarily linked to Asia’s phenomenal economic rise, the speed and scale of which has no parallel in world history.

How fast Asia has come up can be gauged from the 1968 book, Asian Drama: An Inquiry Into the Poverty of Nations, by Swedish economist and Nobel laureate Gunnar Myrdal, who bemoaned the manner impoverishment, population pressures and resource constraints were weighing down Asia. The story of endemic poverty has become a tale of spreading prosperity.

Yet, Asia faces major challenges. It has to cope with entrenched territorial and maritime disputes, harmful historical legacies that weigh down all important interstate Asian relationships, sharpening competition over scarce resources, especially energy and water, growing military capabilities of important Asian actors, increasingly fervent nationalism, and the rise of religious extremism. Diverse trans-border trends — from terrorism and insurgencies, to illicit refugee flows, and human trafficking — add to its challenges.

Asia, however, is becoming more interdependent through trade, investment, technology and tourism. The economic renaissance has been accompanied by the growing international recognition of Asia’s soft power, as symbolized by its arts, fashion and cuisine.

But while Asia is coming together economically, it is not coming together politically. If anything, with the gulf between the politics and economics widening, Asia is becoming more divided politically. In some respects, China’s rise has contributed to making Asia more divided.

To compound matters, there is neither any security architecture in Asia nor a structural framework for regional security. The regional consultation mechanisms remain weak. Differences persist over whether any security architecture or community should extend across Asia or just be confined to an ill-defined regional construct, East Asia. The United States, India, Japan, Vietnam and several other countries wish to treat the Asian continent as a single entity. China, on the other hand, has sought a separate “East Asian” order.

One important point is that while the bloody wars in the first half of the 20th century have made wars unthinkable today in Europe, the wars in Asia in the second half of the 20th century did not resolve matters and have only accentuated bitter rivalries. A number of interstate wars were fought in Asia since 1950, the year both the Korean War and the annexation of Tibet started. Those wars, far from settling or ending disputes, have only kept disputes lingering. China, significantly, was involved in a series of military interventions, even when it was poor and internally troubled.

A Pentagon report released last year has cited examples of how China carried out military preemption in 1950, 1962, 1969 and 1979 in the name of strategic defense. The report states: “The history of modern Chinese warfare provides numerous case studies in which China’s leaders have claimed military preemption as a strategically defensive act. For example, China refers to its intervention in the Korean War (1950-1953) as the ‘War to Resist the United States and Aid Korea.’ Similarly, authoritative texts refer to border conflicts against India (1962), the Soviet Union (1969), and Vietnam (1979) as ‘Self-Defense Counter Attacks’.” The seizure of Paracel Islands from Vietnam in 1974 by Chinese forces was another case of preemption in the name of defense. Against that background, China’s rapidly accumulating power raises important concerns today.

In fact, it is the emergence of China as a major power that is transforming the geopolitical landscape in Asia like no other development. Not since Japan rose to world-power status during the reign of the Meiji Emperor (1867-1912) has another non-Western power emerged with such potential to impact the global order as China today.

But there is an important difference: When Japan rose as a world power, the other Asian civilizations, including the Chinese, Indian and Korean, were in decline. After all, by 19th century, much of Asia, other than Japan and Taiwan, had been colonized by Europeans. So, there was no Asian power that could rein in Japan.

Today, China is rising when other important Asian countries are also rising, including South Korea, Vietnam, India and Indonesia. Although China now has displaced Japan as the world’s second biggest economy, Japan will remain a strong power for the foreseeable future, given its more than $5 trillion economy, Asia’s largest naval fleet, high-tech industries, and a per-capita income still nine times greater than China’s.

When Japan emerged as a world power, its rise opened the path to imperial conquests. However, the expansionist impulses of a rising China are, to some extent, checkmated by the rise of other Asian powers. Militarily, China is in no position to grab the territories it covets, although its defense spending has grown almost twice as fast as its GDP.

Today, as China, India and Japan maneuver for strategic advantage, they are transforming relations between and among themselves in a way that portends closer strategic engagement between New Delhi and Tokyo, and sharper competition between China on one side and Japan and India on the other.

Yet, given the fact that India and China point across the mighty Himalayas in very different geopolitical directions and that Japan and China are separated by sea, they need not pose a threat to each other, especially if they were to abstain from hostile actions against one another and strive to avoid confrontation. The interests of the three powers are getting intertwined to the extent that the pursuit of unilateral solutions by any one of them will disturb the peaceful diplomatic environment on which their continued economic growth and security depend.

Ensuring that the Japan-China and China-India competition does not slide into strategic conflict will nonetheless remain a key challenge in Asia. That, in turn, demands that a strong China, a strong Japan and a strong India find ways to reconcile their interests in Asia so that they can peacefully coexist and prosper.

Never before in history have all three of these powers been strong at the same time. In fact, there is no previous history of the three powers having been involved in a bilateral or trilateral contest for preeminence across Asia.

China’s ascent, however, is dividing Asia, not bringing Asian states closer. By picking territorial fights with its neighbors and pursuing a muscular foreign policy, China is compelling several other Asian states to work closer together with the United States and with each other.

If the Chinese leadership were forward-looking, it would utilize 2011 — the year of the rabbit — to make up for the diplomatic imprudence of 2010 that left an isolated China counting only the problems states of North Korea, Pakistan and Burma as its allies. The onus now is clearly on a rising China to show that it wants to be a responsible power that seeks rules-based cooperation and acts with restraint and caution.

But the People’s Liberation Army’s growing political clout and the sharpening power struggle in the run-up to the major leadership changes scheduled to take place from next year raise concerns that the world will likely see more of what made 2010 a particularly tiger-like year when China frontally discarded Deng Xiaoping’s dictum, tao guang yang hui(conceal ambitions and hide claws).

A tiger’s claws are retractable, but China has taken pride more in baring them than in drawing them in. While manipulating patriotic sentiment, it has pursued hardline policies even at home, tightening its controls on the Internet and media and stepping up repression in Tibet and Xinjiang. China’s domestic policy has a bearing on its external policy, because how it treats its own citizens is an internal dynamic likely to be reflected in the way it deals with its neighbors and other states.

On a host of issues — from diplomacy and territorial claims to trade and currency — China spent 2010 staking out a more-muscular role that only helped heighten international concerns about its rapidly accumulating power and unbridled ambition. But nothing fanned international unease and alarm more than Beijing’s disproportionate response to the Japanese detention of a fishing-trawler captain in September 2010. While Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan’s standing at home took a beating for his meek capitulation to Chinese coercive pressure, the real loser was China, in spite of having speedily secured the captain’s release.

Japan’s passivity in the face of belligerence helped magnify Beijing’s hysterical and menacing reaction. In the process, China not only undercut its international interests by presenting itself as a bully, but it also precipitately exposed the cards it is likely to bring into play when faced with a diplomatic or military crisis next — from employing its trade muscle to inflict commercial pain to exploiting its monopoly on the global production of a vital resource, rare-earth minerals.

Its resort to economic warfare, even in the face of an insignificant provocation, has given other major states advance notice to find ways to offset its leverage, including by avoiding any commercial dependency and reducing their reliance on imports of Chinese rare earths. A more tangible fallout has been that China is already coming under greater international pressure to play by the rules on a host of issues where it has secured unfair advantage — from keeping its currency substantially undervalued to maintaining state subsidies to help its firms win major overseas contracts.

No less revealing has been the gap between China’s words and the reality. For example, China persisted with its unannounced rare-earth embargo against Japan for weeks while continuing to blithely claim the opposite in public — that no export restriction had been imposed. Like its denials last year on two other subjects — the deployment of Chinese troops in Pakistani-held Kashmir to build strategic projects and its use of Chinese convicts as laborers on projects in some countries too poor and weak to protest — China has demonstrated a troubling propensity to obscure the truth.

In fact, the more overtly China has embraced capitalism, the more indigenized it has become ideologically. By progressively turning their back on Marxist dogma —imported from the West — the country’s ruling elites have put Chinese nationalism at the center of their political legitimacy. The new crop of leaders, including President Hu Jintao’s putative successor, Xi Jinping, will bear a distinct nationalistic imprint. Xi is known to be a more assertive personality than Hu.

That suggests that China’s increasingly fractious relations with its neighbors, the U.S. and Europe will likely face new challenges.

More broadly, a fast-rising Asia has become the fulcrum of global geopolitical change. Asian policies and challenges now help shape the international economy and security environment.

Yet major power shifts within Asia are challenging the continent’s own peace and stability. With the specter of strategic disequilibrium looming large in Asia, investments to help build geopolitical stability have become imperative.

China’s lengthening shadow has prompted a number of Asian countries to start building security cooperation on a bilateral basis, thereby laying the groundwork for a potential web of interlocking strategic partnerships. Such cooperation reflects a quiet desire to influence China’s behavior positively, so that it does not cross well-defined red lines or go against the self-touted gospel of its “peaceful rise.”

While the U.S. is thus likely to remain a key factor in influencing Asia’s strategic landscape, the role of the major Asian powers will be no less important. If China, India, and Japan constitute a scalene strategic triangle in Asia, with China representing the longest side, side A, the sum of side B (India) and side C (Japan) will always be greater than A. Not surprisingly, the fastest-growing relationship in Asia today is probably between Japan and India.

If this triangle turned into a quadrangle with the addition of Russia, China would be boxed in from virtually all sides. Japan plus Russia plus India, with the U.S. lending a helpful hand, would not only extinguish any prospect of a Sino-centric Asia, but would create the ultimate strategic nightmare for China. However, a Russian-Japanese rapprochement remains far off.

Against this geopolitical background, Asia’s power dynamics are likely to remain fluid, with new or shifting alliances and strengthened military capabilities continuing to challenge the prevailing regional order.

Brahma Chellaney is the author, most recently, of “Asian Juggernaut: The Rise of China, India and Japan” .

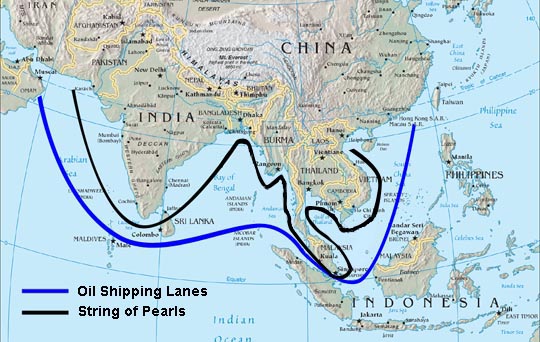

NEW DELHI – International discussion about China’s rise has focused on its increasing trade muscle, growing maritime ambitions, and expanding capacity to project military power. One critical issue, however, usually escapes attention: China’s rise as a hydro-hegemon with no modern historical parallel.

No other country has ever managed to assume such unchallenged riparian preeminence on a continent by controlling the headwaters of multiple international rivers and manipulating their cross-border flows. China, the world’s biggest dam builder – with slightly more than half of the approximately 50,000 large dams on the planet – is rapidly accumulating leverage against its neighbors by undertaking massive hydro-engineering projects on transnational rivers.

Asia’s water map fundamentally changed after the 1949 Communist victory in China. Most of Asia’s important international rivers originate in territories that were forcibly annexed to the People’s Republic of China. The Tibetan Plateau, for example, is the world’s largest freshwater repository and the source of Asia’s greatest rivers, including those that are the lifeblood for mainland China and South and Southeast Asia. Other such Chinese territories contain the headwaters of rivers like the Irtysh, Illy, and Amur, which flow to Russia and Central Asia.

This makes China the source of cross-border water flows to the largest number of countries in the world. Yet China rejects the very notion of water sharing or institutionalized cooperation with downriver countries.

Whereas riparian neighbors in Southeast and South Asia are bound by water pacts that they have negotiated between themselves, China does not have a single water treaty with any co-riparian country. Indeed, having its cake and eating it, China is a dialogue partner but not a member of the Mekong River Commission, underscoring its intent not to abide by the Mekong basin community’s rules or take on any legal obligations.

Worse, while promoting multilateralism on the world stage, China has given the cold shoulder to multilateral cooperation among river-basin states. The lower-Mekong countries, for example, view China’s strategy as an attempt to “divide and conquer.”

Although China publicly favors bilateral initiatives over multilateral institutions in addressing water issues, it has not shown any real enthusiasm for meaningful bilateral action. As a result, water has increasingly become a new political divide in the country’s relations with neighbors like India, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Nepal.

China deflects attention from its refusal to share water, or to enter into institutionalized cooperation to manage common rivers sustainably, by flaunting the accords that it has signed on sharing flow statistics with riparian neighbors. These are not agreements to cooperate on shared resources, but rather commercial accords to sell hydrological data that other upstream countries provide free to downriver states.

In fact, by shifting its frenzied dam building from internal rivers to international rivers, China is now locked in water disputes with almost all co-riparian states. Those disputes are bound to worsen, given China’s new focus on erecting mega-dams, best symbolized by its latest addition on the Mekong – the 4,200-megawatt Xiaowan Dam, which dwarfs Paris’s Eiffel Tower in height – and a 38,000-megawatt dam planned on the Brahmaputra at Metog, close to the disputed border with India. The Metog Dam will be twice as large as the 18,300-megawatt Three Gorges Dam, currently the world’s largest, construction of which uprooted at least 1.7 million Chinese.

In addition, China has identified another mega-dam site on the Brahmaputra at Daduqia, which, like Metog, is to harness the force of a nearly 3,000-meter drop in the river’s height as it takes a sharp southerly turn from the Himalayan range into India, forming the world’s longest and steepest canyon. The Brahmaputra Canyon – twice as deep as the Grand Canyon in the United States – holds Asia’s greatest untapped water reserves.

The countries likely to bear the brunt of such massive diversion of waters are those located farthest downstream on rivers like the Brahmaputra and Mekong – Bangladesh, whose very future is threatened by climate and environmental change, and Vietnam, a rice bowl of Asia. China’s water appropriations from the Illy River threaten to turn Kazakhstan’s Lake Balkhash into another Aral Sea, which has shrunk to less than half its original size.

In addition, China has planned the “Great Western Route,” the proposed third leg of the Great South-North Water Diversion Project – the most ambitious inter-river and inter-basin transfer program ever conceived – whose first two legs, involving internal rivers in China’s ethnic Han heartland, are scheduled to be completed within three years. The Great Western Route, centered on the Tibetan Plateau, is designed to divert waters, including from international rivers, to the Yellow River, the main river of water-stressed northern China, which also originates in Tibet.

With its industry now dominating the global hydropower-equipment market, China has also emerged as the largest dam builder overseas. From Pakistani-held Kashmir to Burma’s troubled Kachin and Shan states, China has widened its dam building to disputed or insurgency-torn areas, despite local backlashes.

For example, units of the People’s Liberation Army are engaged in dam and other strategic projects in the restive, Shia-majority region of Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan-held Kashmir. And China’s dam building inside Burma to generate power for export to Chinese provinces has contributed to renewed bloody fighting recently, ending a 17-year ceasefire between the Kachin Independence Army and the government.

As with its territorial and maritime disputes with India, Vietnam, Japan, and others, China is seeking to disrupt the status quo on international-river flows. Persuading it to halt further unilateral appropriation of shared waters has thus become pivotal to Asian peace and stability. Otherwise, China is likely to emerge as the master of Asia’s water taps, thereby acquiring tremendous leverage over its neighbors’ behavior....

No comments:

Post a Comment